Coordinate Systems for Modeling Microscope Objectives

A common model for infinity corrected microscope objectives is that of an aplanatic and telecentric optical system. In many developments of this model, emphasis is placed upon the calculation of the electric field near the focus. However, this has the effect that the definition of the coordinate systems and geometry are conflated with the determination of the fields. In addition, making the model amenable to computation often occurs as an afterthought.

In this post I will explore the geometry of an aplanatic system for modeling high NA objectives with an emphasis on computational implementations. My approach follows Novotny and Hecht1 and Herrera and Quinto-Su2.

The Model Components

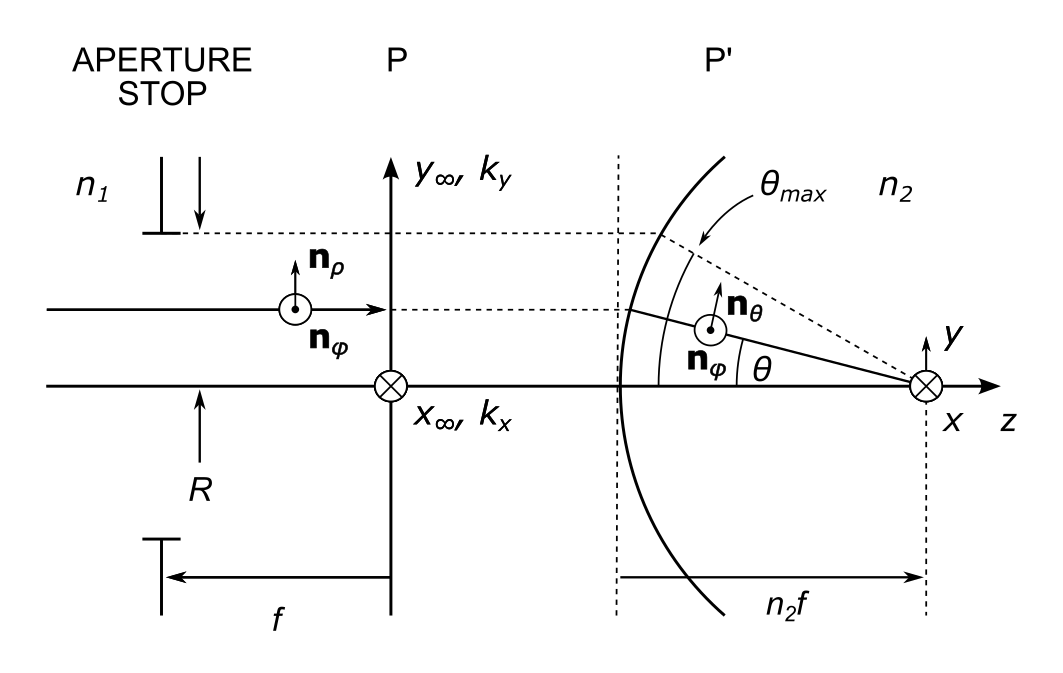

The model system is illustrated below:

In this model, we abstract over the details of the objective by representing it as four surfaces:

- A back focal plane containing an aperture stop

- A back principal plane, \( P \)

- A front principal surface, \( P' \)

- A front focal plane

The space to the left of the back principal plane is called the infinity space. The space to the right of the front principal surface is called the sample space.

We let the infinity space refractive index \( n_1 = 1 \) because it is in air. The refractive index \( n_2 \) is the refractive index of the immersion medium.

The unit vectors \( \mathbf{n} \) are not used in this discussion; they are relevant for computing the fields.

Assumptions

We make one assumption: the system obeys the sine condition. The meaning of this will be explained later.

An aplanatic system is one that obeys the sine condition.

We will not assume the intensity law to conserve energy because it is only necessary when computing the electric field near the focus.

The Aperture Stop and Back Focal Plane

The aperture stop (AS) of an optical system is the element that limits the angle of the marginal ray.

The system is telecentric because the aperture stop is located in the back focal plane (BFP). We can shape the focal field by spatially modulating any of the amplitude, phase, or polarization of the incident light in a plane conjugate to the BFP.

The Back Principal Plane

This is the plane in infinity space at which rays appear to refract. It is a plane because rays coming from a point in the front focal plane all emerge into the infinity space in the same direction.

Strictly speaking, focus field calculations require us to propagate the field from the AS to the back principal plane before computing the Debye diffraction integral, but this step is often omitted3. The assumptions of paraxial optics should hold here.

The Front Principal Surface

The front principal surface is the surface at which rays appear to refract in the sample space. It is a surface because

- this is a non-paraxial system, and

- we assumed the sine condition.

The sine condition states that refraction of a ray coming from an on-axis point in the front focal plane occurs on a spherical cap centered upon the focal point. The distance from the optical axis of the point of intersection of the ray with the surface is proportional to the sine of the angle that the ray makes with the axis.

The principal surface is in the far field of the electric field coming from the focal region. For this reason, we can represent a point on this surface as representing a single ray or a plane wave1.

The Front Focal Plane

This plane is located a distance \( n_2 f \) from the principal surface4. It is not at a distance \( f \) from this surface. This is a result of imaging in an immersion medium.

Geometry and Coordinate Systems

The Aperture Stop Radius

The aperture stop radius \( R \) corresponds to the distance from the axis to the point where the marginal ray intersects the front prinicpal surface. In the sample space, the marginal ray travels at an angle \( \theta_{max} \) with respect to the axis.

Under the sine condition, this height is

$$ R = n_2 f \sin{ \theta_{max} } = f \, \text{NA} $$

The right-most expression uses the definition of the numerical aperture \( \text{NA} \equiv n \sin{ \theta_{max} } \).

Compare this result to the oft-cited expression for the entrance pupil diameter of an objective lens: \( D = 2 f \, \text{NA} \). They are the same. This makes sense because an entrance pupil is either

- an image of an aperture stop, or

- a physical stop.

The Back Principal Plane

There are two independent coordinate systems in the back principal plane:

- the spatial coordinate system defining the far field positions \( \left( x_{\infty} , y_{\infty} \right) \), and

- the coordinate system of the angular spectrum of plane waves \( \left( k_x, k_y \right) \).

The Far Field Coordinate System

The far field coordinate system may be written in Cartesian form as \( \left( x_{\infty} , y_{\infty} \right) \). It also has a cylindrical representation as

$$\begin{eqnarray} \rho &=& \sqrt{x_{\infty}^2 + y_{\infty}^2} \\ \phi &=& \arctan \left( \frac{y_{\infty}}{x_{\infty}} \right) \end{eqnarray}$$

The cylindrical representation appears to be preferred in textbook developments of the model. The Cartesian representation is likely preferred for computational models because it works naturally with two-dimensional arrays of numbers, and because beam shaping elements such as spatial light modulators are rectangular arrays of pixels2.

The Angular Spectrum Coordinate System

Each point in the angular spectrum coordinate system represents a plane wave in the sample space that is traveling at an angle \( \theta \) to the axis according to:

$$\begin{eqnarray} k_x &=& k \sin \theta \cos \phi \\ k_y &=& k \sin \theta \sin \phi \\ k_z &=& k \cos \theta \end{eqnarray}$$

where \( k = 2 \pi n_2 / \lambda = n_2 k_0 \).

Along the y-axis ( \( x_{\infty} = 0 \) ), the maximum value of \( k_y \) is \(n_2 k_0 \sin \theta_{max} = k_0 \, \text{NA} \).

Substitute in the expression \( \text{NA} = R / f \) and we get \(k_{y, max} = k_0 R / f\). But \( R = y_{\infty, max} \). This (and similar reasoning for the x-axis) implies that:

$$\begin{eqnarray} k_x &=& k_0 x_{\infty} / f \\ k_y &=& k_0 y_{\infty} / f \end{eqnarray}$$

The above equations link the angular spectrum coordinate system to the far field coordinate system. They are no longer independent once \( f \) and \( \lambda \) are specified.

Numerical Meshes

There are four free parameters for defining the coordinate systems of the numerical meshes:

- The numerical aperture, \( \text{NA} \)

- The wavelength, \( \lambda \)

- The focal length, \( f \)

- The linear mesh size, \( L \)

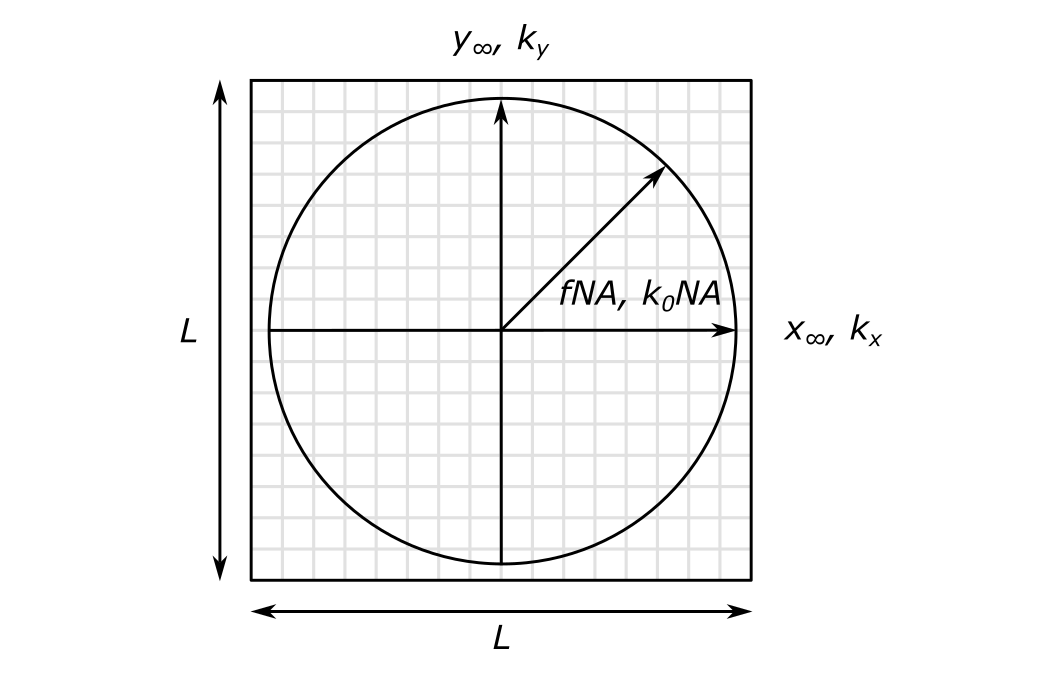

Below is a figure that illustrates the construction of the meshes. Both the far field and angular spectrum coordinate systems are represented by a \( L \times L \) array. \( L = 16 \) in the figure below. In general the value of \( L \) should be a power of 2 to help ensure the efficiency of the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). By considering only powers of 2, we need only consider arrays of even size as well.

The fields are defined on a region of circular support that is centered on this array. The radius of the domain of the far field coordinate system is \( f \text{NA} \); the radius of the domain of the angular spectrum coordinate system is \( k_0 \text{NA} \).

The boxes that are bound by the gray lines indicate the location of each field sample. The \( \left( x_{\infty} , y_{\infty} \right) \) and the \( \left( k_x, k_y \right) \) coordinate systems are sampled at the center of each gray box. The origin is therefore not sampled, which will help avoid division by zero errors when the fields are eventually computed.

The figure suggests that we could create only one mesh and scale it by either \( f \text{NA} \) or \( k_0 \text{NA} \) depending on which coordinate system we are working with. The normalized coordinates become \( \left( x_{\infty} / \left( f \text{NA} \right), y_{\infty} / \left( f \text{NA} \right) \right) \) and \( \left( k_x / \left( k_0 \text{NA} \right), k_y / \left( k_0 \text{NA} \right) \right) \).

1D Mesh Example

As an example, let \( L = 16 \). To four decimal places, the normalized coordinates are \( -1.0000, -0.8667, \ldots, -0.0667, 0.0667, \ldots, 0.8667, 1.0000 \).

The spacing between array elements is \( 2 / \left( L - 1 \right) = 0.1333 \). Note that 0 is not included in the 1D mesh as it goes from -0.0667 to 0.0667.

A 2D mesh is easily constructed from the 1D mesh using tools such as NumPy's meshgrid.

Back Principal Plane Mesh Spacings

In the x-direction, the mesh spacing of the far field coordinate system is

$$ \Delta x_{\infty} = 2 R / \left( L - 1 \right) = 2 f \text{NA} / \left( L - 1 \right) $$

In the \( k_x \)-direction, the mesh spacing of the angular spectrum coordinate system is

$$ \Delta k_x = 2 k_{max} / \left( L - 1 \right) = 2 k_0 \text{NA} / \left( L - 1 \right) $$

Note the symmetry between these two expressions. One scales with \( f \text{NA} \) and the other \( k_0 \text{NA} \). Recall that these are free parameters of the model.

Sample Space Mesh Spacing

It is interesting to compute the spacing between mesh elements \( \Delta x \) in the sample space when the fields are eventually computed.

The sampling angular frequency in the sample space is \( k_S = 2 \pi / \Delta x \).

The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theory states that the maximum informative angular frequency is \( k_{max} = k_S / 2 \).

From the previous section, we know that \( k_{max} = \left(L - 1 \right) \Delta k_x / 2 \), and that \( \Delta k_x = 2 k_0 \text{NA} / \left( L - 1 \right) \).

Combining all the previous expressions and simplifying, we get:

$$\begin{eqnarray} k_S &=& 2 k_{max} \\ 2 \pi / \Delta x &=& \left(L - 1 \right) \Delta k_x \\ 2 \pi / \Delta x &=& \left(L - 1 \right) \left[ 2 k_0 \text{NA} / \left( L - 1 \right) \right] \\ 2 \pi / \Delta x &=& \left(L - 1 \right) \left[ 2 \left(2 \pi / \lambda \right) \text{NA} / \left( L - 1 \right) \right] \end{eqnarray}$$

Solving the above expression for \( \Delta x \), we arrive at

$$ \Delta x = \frac{\lambda}{2 \text{NA}} $$

which is of course the Abbe diffraction limit.

Effect of not Sampling the Origin

Herrera and Quinto-Su2 point out that an error will be introduced if we naively apply the FFT to compute the field components in the \( \left( k_x, k_y \right) \) coordinate system because the origin is not sampled, whereas the FFT assumes that we sample the zero frequency component. The effect is that the result of the FFT has a constant phase error that accounts for a half-pixel shift in each direction of the mesh.

Consider again the 1D mesh example with \(L = 16 \): \( -1.0000, -0.8667, \ldots, -0.0667, 0.0667, \ldots, 0.8667, 1.0000 \)

In Python and other languages that index arrays starting at 0, the origin is located at \(L / 2 - 0.5 \), i.e. halfway between the samples at index 7 and 8. A lateral shift in Fourier space is equivalent to a phase shift in real space:

$$ \phi_{shift} \left(X, Y \right) = -j 2 \pi \frac{0.5}{L} X - j 2 \pi \frac{0.5}{L} Y $$

where \( X \) and \( Y \) are normalized coordinates.

At this point, I am uncertain whether the phasor with the above argument needs to be multiplied or divided with the result of the FFT because 1. there are a few typos in the signs for the coordinate system bounds in the manuscript of Herrera and Quinto-Su, and 2. the correction was developed for use in MATLAB, which indexes arrays starting at 1. Once the fields are computed, it would be easy to verify the correct sign of the phase terms following the procedure outlined in Figure 3 of Herrera and Quinto-Su's manuscript.

Structure of the Algorithm

The algorithm to compute the focus fields will proceed as follows:

- (optional) Propgate the inputs fields from the AS to the back principal plane using paraxial wave propagation

- Input the sampled fields in the back principal plane in the \( \left( x_{\infty}, y_{\infty} \right) \) coordinate system

- Transform the fields to the \( \left( k_x, k_y \right) \) coordinate system

- Compute the fields in the \( \left(x, y, z \right) \) coordinate system using the FFT

Additional Remarks

- Zero padding the mesh will increase the sample space resolution beyond the Abbe limit, but since the fields remain zero outside of the support, no new information is added.

- On the other hand, zero padding might be required when computing fields going from the sample space to the back principal plane to faithfully reproduce any evanescent components.

- Separating the coordinate system and mesh construction from the calculation of the fields reveals that the two assumptions of the model belong separately to each part. The sine condition is used in the construction of the coordinate systems, whereas energy conservation is used when computing the fields.

- This post did not explain how to compute the fields.

- Herrera and Quinto-Su (and possibly also Novotny and Hecht) appear to use an "effective" focal length which can be obtained by multiplying the one that I use by the sample space refractive index. I prefer my formulation because it is consistent with geometric optics and the well-known expression for the diameter of an objective's entrance pupil. When the fields are calculated, however, I do not yet know whether the arguments of the phasors of the Debye integral will require modification.

-

Lukas Novotny and Bert Hecht, "Principles of Nano-Optics," Cambridge University Press (2006). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511813535 ↩↩

-

Isael Herrera and Pedro A. Quinto-Su, "Simple computer program to calculate arbitrary tightly focused (propagating and evanescent) vector light fields," arXiv:2211.06725 (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2211.06725 ↩↩↩

-

Marcel Leutenegger, Ramachandra Rao, Rainer A. Leitgeb, and Theo Lasser, "Fast focus field calculations," Opt. Express 14, 11277-11291 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.14.011277 ↩

-

Sun-Uk Hwang and Yong-Gu Lee, "Simulation of an oil immersion objective lens: A simplified ray-optics model considering Abbe’s sine condition," Opt. Express 16, 21170-21183 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.16.021170 ↩

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus