Meta-Biophysics of the Cell

I work in a biophysics lab applying microscopy techniques to study cell biology. I am not a biologist, and I was not trained as one. I therefore have had to develop heuristics to help me understand what cell biologists do and to communicate with them effectively.

In this post, I present these heuristics as a sort of model for how I think that cell biologists think. I collectively call them "Meta-Biophysics of the Cell" because:

- they model the models of cell biologists, hence they are a meta-model,

- they are inspired by physics and quantitative modeling, and

- I limit myself to cellular processes and not, for example, in vitro or organismal studies.

Furthermore, they are heavily biased by my work in microscopy.

These heuristics may very well be wrong. I do not pretend to understand biology nearly as well as a biologist. If you think I am wrong, please do not hesitate to leave a comment and explain why.

They also are certainly not complete. I present here only what I think the most important heuristics are.

Biologists want to know distributions of proteins across space and time

Cell biology is concerned with understanding the structure and behavior of cells as complex phenomena that emerge from the interactions of molecules. The types of these molecules may be proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, or some other type. I will use the term "protein" generally because

- it's easier than always listing all the types of molecules,

- it's more precise than just saying "molecule"

- there are at least 10,000 different types of proteins in the human cell, making proteins a core building block of the cell, and

- these heuristics do not change if you substitute another type of molecule for the word "protein."

Within a single cell, we can model the number of proteins at a point in space and a point in time with a function \( N \left( \mathbf{r}, t \right) \). This is a spatiotemporal distribution for protein number density. Its dimensions are in numbers of proteins per unit of volume.

A single protein can be represented as a point in space and time, such as a delta function:

$$ N \left( \mathbf{r}, t \right) = \delta \left( \mathbf{r}, t \right) $$

Of course a real protein occupies some volume and is not a point, but at the level of a cell I think that this is an adequate model for what cell biologists want to know about protein distributions.

But wait. There are more than ten thousand types of proteins within the cell. Some proteins are of high abundance, and some are very rare. So it is not sufficient merely to count proteins in space and time: we also need to identify their types. For this, I assign a unique ID to each type that I call \( s \) for "species". Our model now becomes a function of another variable, one that is categorical rather than continuous:

$$ N \left( \mathbf{r}, t ; s\right) $$

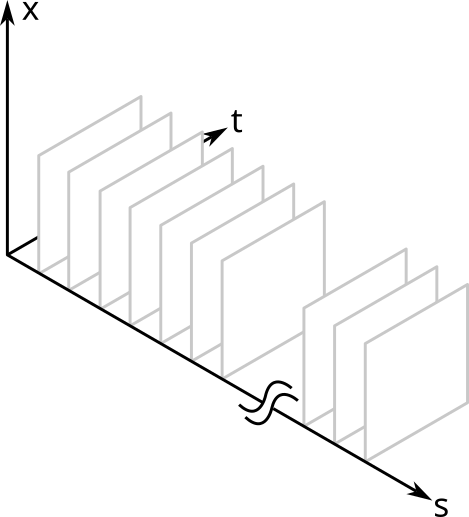

Below I show a simplified schematic of the volume that this model occupies. It is simplified because I show only one spatial dimension (otherwise it would be a five dimensional hypervolume). I saw a figure like this once in a paper about a decade ago, but sadly I cannot find it to credit it. (Update 2025-01-30: The paper referred to is Megason and Fraser, "Imaging in Systems Biology," Cell 130(5), 784-795 (2007))

The \( x \) and \( t \) dimensions are continuous; the \( s \) dimension is a discrete, categorical variable. Each \( s \) slice is the spatiotemporal distribution of that protein within a single cell. Each point in the volume is the protein density for that point in space and time and for that species of protein.

Individual proteins might also vary amongst themselves as in, for example, post translation modifications. This is not really a problem for the above model because we can use a different value for the \( s \) of each variant.

Creation and degradation of a protein

The appearance and disappearance of a protein is modeled as a non-zero value over a time range from \( t_0 \) to \( t_1 \). For example, a single protein existing over a finite time interval may be expressed as

$$\begin{eqnarray} &&\delta \left( \mathbf{r}, t \right), \, t_0 < t < t_1 \\ &&0, \, \text{otherwise} \end{eqnarray}$$

Biologists can only measure slices of protein distributions

Look again at the figure above. Remember that there are in fact five dimensions. Can any one experimental technique measure the whole hypevolume?

No. Instead, biologists can measure slices from the volume and try to piece together a complete picture of \( N \) from individual measurements.

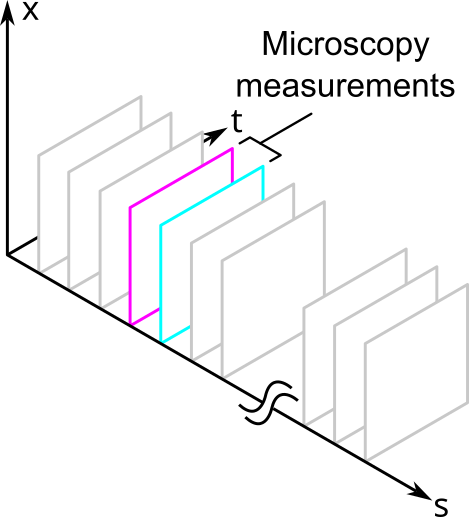

For example, fluorescence microscopy can measure proteins in space and time. Sometimes it can measure in 3 spatial dimensions, but it is easier to measure in 2. Unfortunately, it can only measure a small of number of protein species relative to all the proteins that are in the cell. These would correspond to the different fluorescence channels of the measurement. Thus, fluorescence microscopy provides a slice of the volume that looks like the following:

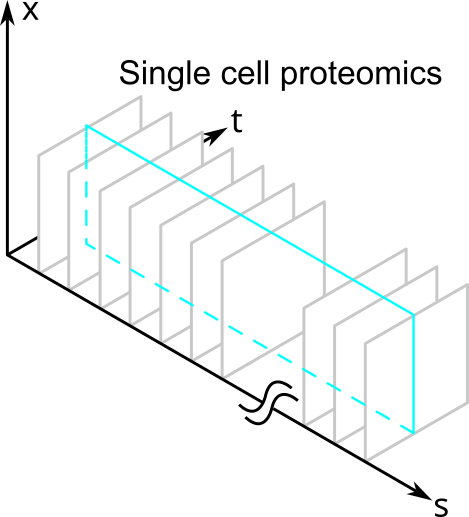

Other types of measurements, such as those in single cell proteomics, might measure a large number of proteins but cannot resolve them in space and time. They would slice the volume like this:

So after their measurements, biologists are always going to be left with less than the total amount of information contained within a single cell because they can only measure slices of \( N \).

Organelles are mutually exclusive slices of protein distributions in space

Consider a mitochondrion. It is a membrane-bound organelle. Everything inside the mitochondrion is considered part of the organelle, and everything outside it is not. An organelle is therefore a mutually-exclusive slice through the volume dimensions of \( N \).

The slices are mutually-exclusive because two mitochondria cannot occupy the same volume at the same time and have a distinct identity.

For non-membrane bound organelles, keep reading.

Organelles contain many types proteins

If we use the definition of an organelle as a mutually-exclusive slice through the volume dimensions of \( N \), then we can look sideways along the \( s \) dimension to find all the proteins that belong to the organelle. If the distribution for protein \( s_i \) is non-zero inside an organelle's volume at a given time, then it belongs to the organelle. The set of all proteins within the volume slice at a given time constitute the organelle.

Knowing \( N \) doesn't by itself tell us what is and is not an organelle

Membrane-bound organelles are easy to identify because of their structure. Other sets of proteins within a given volume may or may not form an organelle. In these situations, we might look at their function instead to decide whether the volume is or is not occupied by an organelle.

For example, organelles like the centrosome have a diffuse, pericentriolar material that surround them. In this case, the border defining what is and isn't inside the centrosome is likely to be somewhat arbitrary.

Cause and Effect is the probability of one protein distribution given another

At this time, I am much less certain about how function and causal relationships fit within this model. It is nevertheless important because biologists are deeply interested in the function of proteins and other complexes. To a rough approximation, I would say that cause and effect describes how the spatiotemporal distributions of a subset of protein species can serve as a predictor of another distribution at a later time. In other words, we can assign a probability to a certain distribution given another one.

I would guess that not every possible set proteins is linked by causal relationships. This would mean that the limitations that come from being able to sample slices of the protein distribution hypervolume are not so significant. You would then want choose your measurements so that you slice the volume to include only the species that are causally linked for the phenomenon that you are studying.

As a consequence of this, the causal links between distributions are likely more important than knowing \( N \). I doubt that we can have a satisfactory understanding of the cell if we could exhaustively measure \( N \) for even a single cell.

Interactions between proteins require spatial colocalization

Protein-protein interactions occur on length-scales on the order of the size of individual proteins. For two different proteins to "interact" we require that they be colocated less than this distance. Colcalization means that two proteins are located less than the distance required for an interaction to occur.

Furthermore, colocalization is necessary but not sufficient for an interaction. A real interaction involves the chemistry between the two different species.

Summary

In summary, my main three heuristics for meta-biophysics of the cell are:

- Biologists want to know distributions of proteins across space and time

- Organelles are mutually exclusive slices of protein distributions in space

- Cause and Effect is the probability of one or more protein distributions given another

I find that nearly all the problems that the cell biologists that I work with can be reformulated into this language. I emphasize again that the "real" science is being done by the biologists, and I in no way mean to diminish the complexity of their work. These heuristics are merely a tool that I use to understand what they are doing when I myself am unfamiliar with their jargon and mental models.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus